Introduction

Regular expressions (“regexes”) allow defining a pattern and executing it against strings. Substrings which match the pattern are termed “matches”.

A regular expression is a sequence of characters that define a search pattern.

Regex finds utility in:

- input validation

- find-replace operations

- advanced string manipulation

- file search or rename

- whitelists and blacklists

- …

Simultaneously, regular expressions are ill-suited for other kinds of problems:

- parsing XML or HTML

- exactly matching dates

- …

There are several regex implementations—regex engines—each with its own quirks and features. This book will avoid going into the differences between these, instead sticking to features that are, for the most part, common across engines.

The example blocks throughout the book use JavaScript under the hood. As a result, the book may be slightly biased towards JavaScript’s regex engine.

Basics

Regular expressions are typically formatted as /<rules>/<flags>. Often people will drop the slashes and flags for brevity. We’ll get into the details of flags in a later chapter.

Let’s start with the regex /p/g. For now, please take the g flag for granted.

/p/g- 1 match

pancake - 3 matches

pineapple - 2 matches

apple - 0 matches

mango - 0 matches

Plum

As we can see, /p/g matches all lowercase p characters.

Regular expressions are case-sensitive by default.

Instances of the regex pattern found in an input string are termed “matches”.

/pp/g- 1 match

apple - 1 match

pineapple - 1 match

happiness - 2 matches

sipping apple juice - 0 matches

papaya

Character Classes

It’s possible to match a character from within a set of characters.

/[aeiou]/g- 4 matches

avocado - 2 matches

brinjal - 3 matches

onion - 0 matches

rhythm

/[aeiou]/g matches all vowels in our input strings.

Here’s another example of these in action:

/p[aeiou]t/g- 1 match

pat - 1 match

pet - 1 match

pit - 1 match

spat - 2 matches

spot a pet - 0 matches

bat

We match a p, followed by one of the vowels, followed by a t.

There’s an intuitive shortcut for matching a character from within a continuous range.

/[a-z]/g- 5 matches

john_s - 5 matches

matej29 - 5 matches

Ayesha?! - 0 matches

4952 - 0 matches

LOUD

The regex /[a-z]/g matches only one character. In the example above, the strings have several matches each, each one character long. Not one long match.

We can combine ranges and individual characters in our regexes.

/[A-Za-z0-9_-]/g- 6 matches

john_s - 7 matches

matej29 - 6 matches

Ayesha?! - 4 matches

4952 - 4 matches

LOUD

Our regex /[A-Za-z0-9_-]/g matches a single character, which must be (at least) one of the following:

- from

A-Z - from

a-z - from

0-9 - one of

_and-.

We can also “negate” these rules:

/[^aeiou]/g- 6 matches

Umbrella - 6 matches

cauliflower - 0 matches

ou

The only difference between the first regex of this chapter and /[^aeiou]/g is the ^ immediately after the opening bracket. Its purpose is to negate the rules defined within the brackets. We are now saying:

“match any character that is not any of

a,e,i,o, andu”

Examples

Prohibited username characters

/[^a-zA-Z_0-9-]/g- 0 matches

TheLegend27 - 0 matches

WaterGuy12 - 0 matches

Smokie_Bear - 7 matches

Robert'); DROP TABLE Students;--

Unambiguous characters

/[A-HJ-NP-Za-kmnp-z2-9]/g- 1 match

foo - 2 matches

lily - 0 matches

lI0O1 - 11 matches

unambiguity

Character Escapes

Character escapes act as shorthands for some common character classes.

Digit character — \d

The character escape \d matches digit characters, from 0 to 9. It is equivalent to the character class [0-9].

/\d/g- 4 matches

2020 - 6 matches

100/100 - 3 matches

It costs $5.45 - 6 matches

3.14159

/\d\d/g- 2 matches

2020 - 2 matches

100/100 - 1 match

It costs $5.45 - 2 matches

3.14159

\D is the negation of \d and is equivalent to [^0-9].

/\D/g- 0 matches

2020 - 1 match

100/100 - 11 matches

It costs $5.45 - 1 match

3.14159

Word character — \w

The escape \w matches characters deemed “word characters”. These include:

- lowercase alphabet —

a–z - uppercase alphabet —

A–Z - digits —

0–9 - underscore —

_

It is thus equivalent to the character class [a-zA-Z0-9_].

/\w/g- 6 matches

john_s - 7 matches

matej29 - 6 matches

Ayesha?! - 4 matches

4952 - 4 matches

LOUD - 4 matches

lo-fi - 6 matches

get out - 6 matches

21*2 = 42(1)

/\W/g- 0 matches

john_s - 2 matches

Ayesha?! - 0 matches

4952 - 0 matches

LOUD - 1 match

lo-fi - 1 match

get out - 3 matches

;-; - 6 matches

21*2 = 42(1)

Whitespace character — \s

The escape \s matches whitespace characters. The exact set of characters matched is dependent on the regex engine, but most include at least:

- space

- tab —

\t - carriage return —

\r - new line —

\n - form feed —

\f

Many also include vertical tabs (\v). Unicode-aware engines usually match all characters in the separator category.

The technicalities, however, will usually not be important.

/\s/g- 1 match

word word - 2 matches

tabs vs spaces - 0 matches

snake_case.jpg

/\S/g- 8 matches

word word - 12 matches

tabs vs spaces - 14 matches

snake_case.jpg

Any character — .

While not a typical character escape, . matches any1 character.

/./g- 6 matches

john_s - 8 matches

Ayesha?! - 4 matches

4952 - 4 matches

LOUD - 5 matches

lo-fi - 7 matches

get out - 3 matches

;-; - 12 matches

21*2 = 42(1)

- Except the newline character

\n. This can be changed using the “dotAll” flag, if supported by the regex engine in question.↩

Escapes

In regex, some characters have special meanings as we will explore across the chapters:

|{,}(,)[,]^,$+,*,?\.— Literal only within character classes.1-— Sometimes a special character within character classes.

When we wish to match these characters literally, we need to “escape” them.

This is done by prefixing the character with a \.

/\(paren\)/g- 0 matches

paren - 0 matches

parents - 1 match

(paren) - 1 match

a (paren)

/(paren)/g- 1 match

paren - 1 match

parents - 1 match

(paren) - 1 match

a (paren)

/example\.com/g- 1 match

example.com - 1 match

a.example.com/foo - 0 matches

example_com - 0 matches

example@com - 0 matches

example_com/foo

/example.com/g- 1 match

example.com - 1 match

a.example.com/foo - 1 match

example_com - 1 match

example@com - 1 match

example_com/foo

/A\+/g- 1 match

A+ - 1 match

A+B - 1 match

5A+ - 0 matches

AAA

/A+/g- 1 match

A+ - 1 match

A+B - 1 match

5A+ - 1 match

AAA

/worth \$5/g- 1 match

worth $5 - 1 match

worth $54 - 1 match

not worth $5

/worth $5/g- 0 matches

worth $5 - 0 matches

worth $54 - 0 matches

not worth $5

Examples

JavaScript in-line comments

/\/\/.*/g- 1 match

console.log(); // comment - 1 match

console.log(); // // comment - 0 matches

console.log();

Asterisk-surrounded substrings

/\*[^\*]*\*/g- 1 match

here be *italics* - 1 match

permitted** - 1 match

a*b*c*d - 2 matches

a*b*c*d*e - 0 matches

a️bcd

The first and last asterisks are literal since they are escaped — \*.

The asterisk inside the character class does not necessarily need to be escaped1, but I’ve escaped it anyway for clarity.

The asterisk immediately following the character class indicates repetition of the character class, which we’ll explore in chapters that follow.

- Many special characters that would otherwise have special meanings are treated literally by default inside character classes.↩

Groups

Groups, as the name suggests, are meant to be used to “group” components of regular expressions. These groups can be used to:

- Extract subsets of matches

- Repeat groups an arbitrary number of times

- Refer to previously matched substrings

- Enhance readability

- Allow complex alternations

We’ll see how to do a lot of this in later chapters, but learning how groups work will allow us to study some great examples in these later chapters.

Capturing groups

Capturing groups are denoted by ( … ). Here’s an expository example:

/a(bcd)e/g- 1 match

abcde - 1 match

abcdefg? - 1 match

abcde

Capturing groups allow extracting parts of matches.

/\{([^{}]*)\}/g- 1 match

{braces} - 2 matches

{two} {pairs} - 1 match

{ {nested} } - 1 match

{ incomplete } } - 1 match

{} - 0 matches

{unmatched

Using your language’s regex functions, you would be able to extract the text between the matched braces for each of these strings.

Capturing groups can also be used to group regex parts for ease of repetition of said group. While we will cover repetition in detail in chapters that follow, here’s an example that demonstrates the utility of groups.

/a(bcd)+e/g- 1 match

abcdefg - 1 match

abcdbcde - 1 match

abcdbcdbcdef - 0 matches

ae

Other times, they are used to group logically similar parts of the regex for readability.

/(\d\d\d\d)-W(\d\d)/g- 1 match

2020-W12 - 1 match

1970-W01 - 1 match

2050-W50-6 - 1 match

12050-W50

Backreferences

Backreferences allow referring to previously captured substrings.

The match from the first group would be \1, that from the second would be \2, and so on…

/([abc])=\1=\1/g- 1 match

a=a=a - 1 match

ab=b=b - 0 matches

a=b=c

Backreferences cannot be used to reduce duplication in regexes. They refer to the match of groups, not the pattern.

/[abc][abc][abc]/g- 1 match

abc - 1 match

a cable - 1 match

aaa - 1 match

bbb - 1 match

ccc

/([abc])\1\1/g- 0 matches

abc - 0 matches

a cable - 1 match

aaa - 1 match

bbb - 1 match

ccc

Here’s an example that demonstrates a common use-case:

/\w+([,|])\w+\1\w+/g- 1 match

comma,separated,values - 1 match

pipe|separated|values - 0 matches

wb|mixed,delimiters - 0 matches

wb,mixed|delimiters

This cannot be achieved with a repeated character classes.

/\w+[,|]\w+[,|]\w+/g- 1 match

comma,separated,values - 1 match

pipe|separated|values - 1 match

wb|mixed,delimiters - 1 match

wb,mixed|delimiters

Non-capturing groups

Non-capturing groups are very similar to capturing groups, except that they don’t create “captures”. They take the form (?: … ).

Non-capturing groups are usually used in conjunction with capturing groups. Perhaps you are attempting to extract some parts of the matches using capturing groups. You may wish to use a group without messing up the order of the captures. This is where non-capturing groups come handy.

Examples

Query String Parameters

/^\?(\w+)=(\w+)(?:&(\w+)=(\w+))*$/g- 0 matches

- 0 matches

? - 1 match

?a=b - 1 match

?a=b&foo=bar

We match the first key-value pair separately because that allows us to use &, the separator, as part of the repeating group.

(Basic) HTML tags

As a rule of thumb, do not use regex to match XML/HTML.1234

However, it’s a relevant example:

/<([a-z]+)+>(.*)<\/\1>/gi- 1 match

<p>paragraph</p> - 1 match

<li>list item</li> - 1 match

<p><span>nesting</span></p> - 0 matches

<p>hmm</li> - 1 match

<p><p>not clever</p></p></p>

Names

Find: \b(\w+) (\w+)\b

Replace: $2, $15

Before

John Doe

Jane Doe

Sven Svensson

Janez Novak

Janez Kranjski

Tim Joe

After

Doe, John

Doe, Jane

Svensson, Sven

Novak, Janez

Kranjski, Janez

Joe, Tim

Backreferences and plurals

Find: \bword(s?)\b

Replace: phrase$15

Before

This is a paragraph with some words.

Some instances of the word "word" are in their plural form: "words".

Yet, some are in their singular form: "word".

After

This is a paragraph with some phrases.

Some instances of the phrase "phrase" are in their plural form: "phrases".

Yet, some are in their singular form: "phrase".

- https://stackoverflow.com/a/590789↩

- https://stackoverflow.com/a/6751339↩

- https://blog.codinghorror.com/parsing-html-the-cthulhu-way/↩

- https://web.archive.org/web/20071018202901/http://oubliette.alpha-geek.com/2004/01/12/bring_me_your_regexs_i_will_create_html_to_break_them↩

- In replacement contexts,

$1,$2, … are usually used in place of\1,\2, … to refer to captured strings.↩

Repetition

Repetition is a powerful and ubiquitous regex feature. There are several ways to represent repetition in regex.

Making things optional

We can make parts of regex optional using the ? operator.

/a?/g- 1 match

- 2 matches

a - 3 matches

aa - 4 matches

aaa - 5 matches

aaaa - 6 matches

aaaaa

Here’s another example:

/https?/g- 1 match

http - 1 match

https - 1 match

http/2 - 1 match

shttp - 0 matches

ftp

Here the s following http is optional.

We can also make capturing and non-capturing groups optional.

/url: (www\.)?example\.com/g- 1 match

url: example.com - 1 match

url: www.example.com/foo - 1 match

Here's the url: example.com.

Zero or more

If we wish to match zero or more of a token, we can suffix it with *.

/a*/g- 1 match

- 2 matches

a - 2 matches

aa - 2 matches

aaa - 2 matches

aaaa - 2 matches

aaaaa

Our regex matches even an empty string "".

One or more

If we wish to match one or more of a token, we can suffix it with a +.

/a+/g- 0 matches

- 1 match

a - 1 match

aa - 1 match

aaa - 1 match

aaaa - 1 match

aaaaa

Exactly x times

If we wish to match a particular token exactly x times, we can suffix it with {x}. This is functionally identical to repeatedly copy-pasting the token x times.

/a{3}/g- 0 matches

- 0 matches

a - 0 matches

aa - 1 match

aaa - 1 match

aaaa - 1 match

aaaaa

Here’s an example that matches an uppercase six-character hex colour code.

/#[0-9A-F]{6}/g- 1 match

#AE25AE - 1 match

#663399 - 1 match

How about #73FA79? - 1 match

Part of #73FA79BAC too - 0 matches

#FFF - 0 matches

#a2ca2c

Here, the token {6} applies to the character class [0-9A-F].

Between min and max times

If we wish to match a particular token between min and max (inclusive) times, we can suffix it with {min,max}.

/a{2,4}/g- 0 matches

- 0 matches

a - 1 match

aa - 1 match

aaa - 1 match

aaaa - 1 match

aaaaa

There must be no space after the comma in {min,max}.

At least x times

If we wish to match a particular token at least x times, we can suffix it with {x,}. Think of it as {min,max}, but without an upper bound.

/a{2,}/g- 0 matches

- 0 matches

a - 1 match

aa - 1 match

aaa - 1 match

aaaa - 1 match

aaaaa

A note on greediness

Regular expressions, by default, are greedy. They attempt to match as much as possible.

/a*/g- 2 matches

aaaaaa

/".*"/g- 1 match

"quote" - 1 match

"quote", "quote" - 1 match

"quote"quote"

Suffixing a repetition operator (?, *, +, …) with a ?, one can make it “lazy”.

/".*?"/g- 1 match

"quote" - 2 matches

"quote", "quote" - 1 match

"quote"quote"

Here, this could also be achieved by using [^"] instead of . (as is best practice).

/"[^"]*"/g- 1 match

"quote" - 2 matches

"quote", "quote" - 1 match

"quote"quote"

[…] Lazy will stop as soon as the condition is satisfied, but greedy means it will stop only once the condition is not satisfied any more

—Andrew S on StackOverflow

/<.+>/g- 1 match

<em>g r e e d y</em>

/<.+?>/g- 2 matches

<em>lazy</em>

Examples

Bitcoin address

/([13][a-km-zA-HJ-NP-Z0-9]{26,33})/g- 1 match

3Nxwenay9Z8Lc9JBiywExpnEFiLp6Afp8v - 1 match

1HQ3Go3ggs8pFnXuHVHRytPCq5fGG8Hbhx - 1 match

2016-03-09,18f1yugoAJuXcHAbsuRVLQC9TezJ

Youtube Video

/(?:https?:\/\/)?(?:www\.)?youtube\.com\/watch\?.*?v=([^&\s]+).*/gm- 1 match

youtube.com/watch?feature=sth&v=dQw4w9WgXcQ - 1 match

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dQw4w9WgXcQ - 1 match

www.youtube.com/watch?v=dQw4w9WgXcQ - 1 match

youtube.com/watch?v=dQw4w9WgXcQ - 1 match

fakeyoutube.com/watch?v=dQw4w9WgXcQ

We can adjust this to not match the last broken link using anchors, which we shall encounter soon.

Alternation

Alternation allows matching one of several phrases. This is more powerful than character classes, which are limited to characters.

Delimit the set of phrases with pipes—|.

/foo|bar|baz/g- 2 matches

foo baz - 1 match

Your food - 1 match

Behind bars

One of

foo,bar, andbaz

If only a part of the regex is to be “alternated”, wrap that part with a group—capturing or non-capturing.

/Try (foo|bar|baz)/g- 1 match

Try foo - 1 match

Try bar - 1 match

Try baz - 1 match

Try food

Tryfollowed by one offoo,bar, andbaz

Matching numbers between 100 and 250:

/1\d\d|2[0-4]\d|250/g- 3 matches

100, 157, 199 - 2 matches

139 + 140 = 279 - 1 match

201 INR - 1 match

$220 - 1 match

250 - 1 match

1250 - 2 matches

e = 2.71828182... - 0 matches

251 - 0 matches

729

This can be generalized to match arbitrary number ranges!

Examples

Hex colours

Let’s improve one of our older examples to also match shorthand hex colours.

/#([0-9A-F]{6}|[0-9A-F]{3})/g- 1 match

#AE25AE - 1 match

#663399 - 1 match

How about #73FA79? - 1 match

Part of #73FA79BAC too - 1 match

#FFF - 0 matches

#a2ca2c

It is important that [0-9A-F]{6} comes before [0-9A-F]{3}. Else:

/#([0-9A-F]{3}|[0-9A-F]{6})/g- 1 match

#AE25AE - 1 match

#663399 - 1 match

How about #73FA79? - 1 match

Part of #73FA79BAC too - 1 match

#FFF - 0 matches

#a2ca2c

Regex engines try alternatives from the left to the right.

Roman numerals

/^M{0,4}(CM|CD|D?C{0,3})(XC|XL|L?X{0,3})(IX|IV|V?I{0,3})$/g- 1 match

MMXX - 1 match

VI - 1 match

XX - 1 match

XI - 0 matches

IXI - 0 matches

VV

Flags

Flags (or “modifiers”) allow us to put regexes into different “modes”.

Flags are the part after the final / in /pattern/.

Different engines support different flags. We’ll explore some of the most common flags here.

Global (g)

All examples thus far have had the global flag. When the global flag isn’t enabled, the regex doesn’t match anything beyond the first match.

/[aeiou]/g- 3 matches

corona - 2 matches

cancel - 0 matches

rhythm

/[aeiou]/- 1 match

corona - 1 match

cancel - 0 matches

rhythm

(Case) Insensitive (i)

As the name suggests, enabling this flag makes the regex case-insensitive in its matching.

/#[0-9A-F]{6}/i- 1 match

#AE25AE - 1 match

#663399 - 1 match

Even #a2ca2c? - 0 matches

#FFF

/#[0-9A-F]{6}/- 1 match

#AE25AE - 1 match

#663399 - 0 matches

Even #a2ca2c? - 0 matches

#FFF

/#[0-9A-Fa-f]{6}/- 1 match

#AE25AE - 1 match

#663399 - 1 match

Even #a2ca2c? - 0 matches

#FFF

Multiline (m)

In Ruby, the m flag performs other functions.

The multiline flag has to do with the regex’s handling of anchors when dealing with “multiline” strings—strings that include newlines (\n). By default, the regex /^foo$/ would match only "foo".

We might want it to match foo when it is in a line by itself in a multiline string.

Let’s take the string "bar\nfoo\nbaz" as an example:

bar

foo

baz

Without the multiline flag, the string above would be considered as a single line bar\nfoo\nbaz for matching purposes. The regex ^foo$ would thus not match anything.

With the multiline flag, the input would be considered as three “lines”: bar, foo, and baz. The regex ^foo$ would match the line in the middle—foo.

Dot-all (s)

JavaScript, prior to ES2018, did not support this flag. Ruby does not support the flag, instead using m for the same.

The . typically matches any character except newlines. With the dot-all flag, it matches newlines too.

Unicode (u)

In the presence of the u flag, the regex and the input string will be interpreted in a unicode-aware way. The details of this are implementation-dependent, but here are some things to expect:

- Character classes may match astral symbols.

- Character escapes may match astral symbols and may be unicode-aware.

- The

iflag may use Unicode’s case-folding logic. - The use of some features like unicode codepoint escapes and unicode property escapes may be enabled.

Whitespace extended (x)

When this flag is set, whitespace in the pattern is ignored (unless escaped or in a character class). Additionally, characters following # on any line are ignored. This allows for comments and is useful when writing complex patterns.

Here’s an example from Advanced Examples, formatted to take advantage of the whitespace extended flag:

^ # start of line

(

[+-]? # sign

(?=\.\d|\d) # don't match `.`

(?:\d+)? # integer part

(?:\.?\d*) # fraction part

)

(?: # optional exponent part

[eE]

(

[+-]? # optional sign

\d+ # power

)

)?

$ # end of line

Anchors

Anchors do not match anything by themselves. Instead, they place restrictions on where matches may appear—“anchoring” matches.

You could also think about anchors as “invisible characters”.

Beginning of line — ^

Marked by a caret (^) at the beginning of the regex, this anchor makes it necessary for the rest of the regex to match from the beginning of the string.

You can think of it as matching an invisible character always present at the beginning of the string.

/^p/g- 1 match

photoshop - 1 match

pineapple - 0 matches

tap - 0 matches

apple - 1 match

ppap - 0 matches

mango

End of line — $

This anchor is marked by a dollar ($) at the end of the regex. It is analogous to the beginning of the line anchor.

You can think of it as matching an invisible character always present at the end of the string.

/p$/g- 1 match

photoshop - 0 matches

pineapple - 0 matches

apple - 1 match

app - 0 matches

Plum - 0 matches

mango

The ^ and $ anchors are often used in conjunction to ensure that the regex matches the entirety of the string, rather than merely a part.

/^p$/g- 1 match

p - 0 matches

pi - 0 matches

pea - 0 matches

tarp - 0 matches

apple

Let’s revisit an example from Repetition, and add the two anchors at the ends of the regex.

/^https?$/g- 1 match

http - 1 match

https - 0 matches

http/2 - 0 matches

shttp - 0 matches

ftp

In the absence of the anchors, http/2 and shttp would also match.

Word boundary — \b

A word boundary is a position between a word character and a non-word character.

The word boundary anchor, \b, matches an imaginary invisible character that exists between consecutive word and non-word characters.

/\bp/g- 1 match

peach - 1 match

banana, peach - 1 match

banana+peach - 1 match

banana-peach - 0 matches

banana_peach - 0 matches

banana%20peach - 0 matches

grape

Words characters include a-z, A-Z, 0-9, and _.

/\bp\b/g- 1 match

word p word - 1 match

(p) - 1 match

p+q+r - 0 matches

(paren) - 0 matches

(loop) - 0 matches

loops

/\bcat\b/g- 1 match

cat - 1 match

the cat? - 0 matches

catch - 0 matches

concat it - 0 matches

concatenate

There is also a non-word-boundary anchors: \B.

As the name suggests, it matches everything apart from word boundaries.

/\Bp/g- 1 match

ape - 1 match

leap - 1 match

(leap) - 0 matches

a pot - 0 matches

pea

/\Bp\B/g- 1 match

ape - 1 match

_peel - 0 matches

leap - 0 matches

(leap) - 0 matches

a pot - 0 matches

pea

^…$ and \b…\b are common patterns and you will almost always need one or the other to prevent accidental matches.

Examples

Trailing whitespace

/\s+$/gm- 1 match

abc - 1 match

def - 0 matches

abc def

Markdown headings

/^## /gm- 0 matches

# Heading 1 - 1 match

## Heading 2 - 0 matches

### Heading 3 - 0 matches

#### Heading 4

Without anchors:

/## /gm- 0 matches

# Heading 1 - 1 match

## Heading 2 - 1 match

### Heading 3 - 1 match

#### Heading 4

Lookaround

This section is a Work In Progress.

Lookarounds can be used to verify conditions, without matching any text.

You’re only looking, not moving.

- Lookahead

- Positive —

(?=…) - Negative —

(?!…)

- Positive —

- Lookbehind

- Positive —

(?<=…) - Negative —

(?<!…)

- Positive —

Lookahead

Positive

/_(?=[aeiou])/g- 1 match

_a - 1 match

e_e - 0 matches

_f

Note how the character following the _ isn’t matched. Yet, its nature is confirmed by the positive lookahead.

/(.+)_(?=[aeiou])(?=\1)/g- 1 match

e_e - 1 match

u_u - 1 match

uw_uw - 1 match

uw_uwa - 0 matches

f_f - 0 matches

a_e

After (?=[aeiou]), the regex engine hasn’t moved and checks for (?=\1) starting after the _.

/(?=.*#).*/g- 1 match

abc#def - 1 match

#def - 1 match

abc# - 0 matches

abcdef

Negative

/_(?![aeiou])/g- 0 matches

_a - 0 matches

e_e - 1 match

_f

/^(?!.*#).*$/g- 0 matches

abc#def - 0 matches

#def - 0 matches

abc# - 1 match

abcdef

Without the anchors, this will match the part without the # in each test case.

Negative lookaheads are commonly used to prevent particular phrases from matching.

/foo(?!bar)/g- 1 match

foobaz - 0 matches

foobarbaz - 0 matches

bazfoobar

/---(?:(?!---).)*---/g- 1 match

---foo--- - 1 match

---fo-o--- - 1 match

--------

Lookbehind

JavaScript, prior to ES2018, did not support this flag.

Positive

Negative

Examples

Password validation

/^(?=.*\d)(?=.*[a-z])(?=.*[A-Z])(?=.*[a-zA-Z]).{8,}$/- 0 matches

hunter2 - 0 matches

zsofpghedake - 0 matches

zsofpghedak4e - 1 match

zSoFpghEdaK4E - 1 match

zSoFpg!hEd!aK4E

Lookarounds can be used verify multiple conditions.

Quoted strings

/(['"])(?:(?!\1).)*\1/g- 1 match

foo "bar" baz - 1 match

foo 'bar' baz - 1 match

foo 'bat's' baz - 1 match

foo "bat's" baz - 1 match

foo 'bat"s' baz

Without lookaheads, this is the best we can do:

/(['"])[^'"]*\1/g- 1 match

foo "bar" baz - 1 match

foo 'bar' baz - 1 match

foo 'bat's' baz - 0 matches

foo "bat's" baz - 0 matches

foo 'bat"s' baz

Advanced Examples

Javascript comments

/\/\*[\s\S]*?\*\/|\/\/.*/g- 1 match

const a = 0; // comment - 1 match

/* multiline */

[\s\S] is a hack to match any character including newlines. We avoid the dot-all flag because we need to use the ordinary . for single-line comments.

24-Hour Time

/^([01]?[0-9]|2[0-3]):[0-5][0-9](:[0-5][0-9])?$/g- 1 match

23:59:00 - 1 match

14:00 - 1 match

23:00 - 0 matches

29:00 - 0 matches

32:32

Meta

/<Example source="(.*?)" flags="(.*?)">/gm- 1 match

<Example source="p[aeiou]t" flags="g"> - 1 match

<Example source="s+$" flags="gm"> - 1 match

<Example source="(['"])(?:(?!\1).)*\1" flags="g"> - 0 matches

<Example source='s+$' flags='gm'> - 0 matches

</Example>

Replace: <Example regex={/$1/$2}>

I performed this operation in commit d7a684f.

Floating point numbers

- optional sign

- optional integer part

- optional decimal part

- optional exponent part

/^([+-]?(?=\.\d|\d)(?:\d+)?(?:\.?\d*))(?:[eE]([+-]?\d+))?$/g- 1 match

987 - 1 match

-8 - 1 match

0.1 - 1 match

2. - 1 match

.987 - 1 match

+4.0 - 1 match

1.1e+1 - 1 match

1.e+1 - 1 match

1e2 - 1 match

0.2e2 - 1 match

.987e2 - 1 match

+4e-1 - 1 match

-8.e+2 - 0 matches

.

The positive lookahead (?=\.\d|\d) ensures that the regex does not match ..

Latitude and Longitude

/^((-?|\+?)?\d+(\.\d+)?),\s*((-?|\+?)?\d+(\.\d+)?)$/g- 1 match

30.0260736, -89.9766792 - 1 match

45, 180 - 1 match

-90.000, -180.0 - 1 match

48.858093,2.294694 - 1 match

-3.14, 3.14 - 1 match

045, 180.0 - 1 match

0, 0 - 0 matches

-90., -180. - 0 matches

.004, .15

See also: Floating Point Numbers

MAC Addresses

/^[a-f0-9]{2}(:[a-f0-9]{2}){5}$/i- 1 match

01:02:03:04:ab:cd - 1 match

9E:39:23:85:D8:C2 - 1 match

00:00:00:00:00:00 - 0 matches

1N:VA:L1:DA:DD:R5 - 0 matches

9:3:23:85:D8:C2 - 0 matches

ac::23:85:D8:C2

UUID

/[\da-f]{8}-([\da-f]{4}-){3}[\da-f]{12}/i- 1 match

123e4567-e89b-12d3-a456-426655440000 - 1 match

c73bcdcc-2669-4bf6-81d3-e4ae73fb11fd - 1 match

C73BCDCC-2669-4Bf6-81d3-E4AE73FB11FD - 0 matches

c73bcdcc-2669-4bf6-81d3-e4an73fb11fd - 0 matches

c73bcdcc26694bf681d3e4ae73fb11fd

IP Addresses

/\b(?:(?:2(?:[0-4][0-9]|5[0-5])|[0-1]?[0-9]?[0-9])\.){3}(?:(?:2([0-4][0-9]|5[0-5])|[0-1]?[0-9]?[0-9]))\b/g- 1 match

9.9.9.9 - 1 match

127.0.0.1:8080 - 1 match

It's 192.168.1.9 - 1 match

255.193.09.243 - 1 match

123.123.123.123 - 0 matches

123.123.123.256 - 0 matches

0.0.x.0

HSL colours

Integers from 0 to 360

360300to359—3,[0-5], any digit0to299- optionally

1or2as the hundreds digit - optionally any tens digit

- a units digit

- optionally

/^0*(?:360|3[0-5]\d|[12]?\d?\d)$/g- 1 match

360 - 1 match

349 - 1 match

235 - 1 match

152 - 1 match

68 - 1 match

9 - 0 matches

361 - 0 matches

404

Percentages

100, optionally followed by.000…- one or two digit integer, optionally followed decimal part

/^(?:100(?:\.0+)?|\d?\d(?:\.\d+)?)%$/g- 1 match

100% - 1 match

100.0% - 1 match

25% - 1 match

52.32% - 1 match

9% - 1 match

0.5% - 0 matches

100.5% - 0 matches

42

Bringing it all together

/^hsl\(\s*0*(?:360|3[0-5]\d|[12]?\d?\d)\s*(?:,\s*0*(?:100(?:\.0+)?|\d?\d(?:\.\d+)?)%\s*){2}\)$/gi- 1 match

hsl(0,20%,100%) - 1 match

HSL(0350, 002%,4.1%) - 1 match

hsl(360,10% , 0.2% )

Next Steps

Congratulations on getting this far!

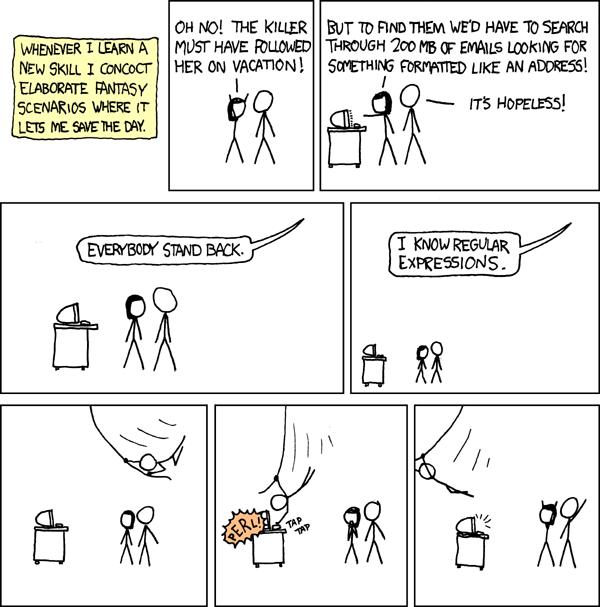

Obligatory xkcd:

If you’d like to read more about regular expressions and how they work:

- awesome-regex

regextag on StackOverflow- StackOverflow RegEx FAQ

- r/regex

- RexEgg

- Regular-Expressions.info

- Regex Crossword

- Regex Golf

Thanks for reading!